Leaning in Old Bavaria

Already in the early medieval duchy of Bavaria elements of feudalism (vassals, benefices) are attested; the classical expression with the combination of both elements apparently came about only in the High Middle Ages. Especially in the High Middle Ages, feudalism had a great importance in building and consolidating aristocratic territorial rule. The late medieval fiefdom of Old Bavaria has been studied so far only in terms of the Wittelsbach dukes. Here, from the 14th century, the large number of rural laissez-passer arises. From the 16th century, the ducal or Electoral feudal system was systematically managed and developed into a pure source of income. During the first half of the 19th century, it was largely abolished. Last fiefs existed until 1919/20.

Table of Contents

The emergence of feudalism

The origins of feudalism go back to two different phenomena, which according to the older research are both dated to the Merovingian period. One of them was of a natural nature and concerned a temporary right to use a piece of land, the "beneficium". The second, the so-called vassalage, was personal: Free went into the protection of other suitors and rendered these war or other services.

According to traditional doctrine (Ganshof, Mitteis) is the real fiefs among the first Carolingian rulers in 8./9. Century from the union of benefit and vassalage emerged. In the Carolingian period, therefore, a rite was formed in which the benefit was conferred and the vassal entered into a personal bond with his feudal lord. This rite was probably hardly changed over centuries. He consisted of the performance of "team" or the "commendation", whereby the vassal laid his hands in the Lord’s favor, out of the allegiance of the vassal and from the symbolic investiture into the benefit or fief (Lippert). From this act emerged a legal relationship in which the vassals to the feudal lord "Advice and help" and the feudal lord to the vassals "Protection and screen" were obliged. The solid grounding of these ritualistic ceremonies made written records on feudalism obsolete for centuries.

The Bavarian feudal system of the early Middle Ages

a) The vassalage – the personal element

There are only a few more exact findings about the early medieval fiefdom in the Agilolfing duchy and in the Carolingian imperial province of Bavaria. At this time, the traditional books of the monasteries and bishoprics represent by far the most important source. The central concepts of early medieval feudalism "Vassi", "Vasalli" and "milites" do not even appear there before the 9th century. Only the 788 deposed Duke Tassilo III. (reigned 748-788, died 794), but only in Franconian annals, as a vassal of Charlemagne (reigned 768-810, emperor from 800) referred. The Adalschalken (Latin "servi principis"), a group of ducal followers named in the eighth century, may have had similar functions as charitable bailiffs; However, this can not be proven.

Vassals appear as such for the first time in 819. Most appear as royal vassals, followed by those of the Bavarian bishops, counts or other nobles. There could be no more ducal vassals, since no independent duchy of the Bavarians existed anymore. The vassals had a high social position. Most of them came from the legal free class, a few also from the then highest class of society "nobiles" (Noble). What services the vassals had to perform, does not emerge from the sources. At best, it can be assumed that these were, above all, martial services.

b) The benefit – the material element

The material side of the fief is in the sense of the legal relationship in the traditional books as "beneficium", the lending process itself with the verb "praestare" designated. Benefizia are – unlike the vassalage – already attested in the first half of the 8th century. As persons who forgave Benefizia, bishops are most often mentioned, which is probably due to the lore. There are also testimonies about ducal and royal charity. After all, the noblemen could certainly distribute Benefizia. Recipients were primarily simple clerics, such as deacons or priests, and higher clergy (especially bishops, occasionally Archipresbyter or Pröpste). Even monks are proven as owners of Benefizia. Moreover, it was very likely that every layman of free standing could receive a benefit; Counters, married couples, women and siblings can also be identified as recipients. Eventually, even the king was granted religious fiefs (eg, Ludwig the German [reg 843-876] of St. Emmeram) – a proof that this was not a strictly hierarchical system.

Episcopal Benefizia were mostly smaller landlordly estates such as farmhouses or farms, but also churches ("private churches") and rare monasteries. In return, usually the payment of an interest is indicated. Services to be provided are only generally considered "servitium" addressed, but unspecified. The recipient of a benefit was also bound to be faithful to the bishop. Episcopal Benefizia were awarded almost exclusively for life. In contrast, those of the Duke were also explicitly equipped with inheritance rights. Likewise, the ducal ones, who came from the Fiskalgut, could be sold or given away with the consent of the Duke, in contrast to the episcopal Benefizia, who came from Kirchengut.

c) Connection of vassalage and benefit?

The vassalage and benefice were not related to each other in early medieval Bavaria: the awarding of a charity was never justified by the vassalage service; neither is the reverse case known. Therefore, recent work emphasizes that it is highly doubtful whether one for the early Middle Ages in Bavaria at all from a "Leaning in the traditional sense" (Deutinger) can speak.

The high medieval feudal system

The long epoch from the 10th to the 13th century, according to the traditional teaching (Ganshof, Mitteis), is considered the classical period of feudalism. Lenten binding was considered the decisive constitutional historical element of the High Middle Ages. This view is probably no longer tenable (Reynolds, conference proceedings Dendorfer / Deutinger). First, it should be emphasized that in the Reich under no circumstances a unified feudal existence existed, but in the various regions of highly diverse and diverse manifestations are detectable. Recent research continues to suggest that north of the Alps and right of the Rhine before the 12th century legal structures based on the combination of vassalage and benefit, can hardly or not even made tangible (Proceedings Dendorfer / Deutinger). Thus, the twelfth century is considered a decisive turning point in the history of feudalism; the older research is to be put to the test.

The same applies to Bavaria: It is only since the middle of the 12th century that a feudal law or feudal law in the classical sense has gained somewhat clearer contours (Seibert). The connection between vassalage and benefit apparently did not become constitutive until the 12th and 13th centuries for a feudal relationship. For Bavaria in particular, however, it must always be emphasized that recent research is just beginning and must therefore always be argued with the utmost caution.

a) 10th and 11th centuries

For the 10th and 11th centuries, it is important in terms of sources, especially on the traditional books, which, however, have not been systematically evaluated in this regard. Characteristic of the first years of Bavaria under the Luitpoldingern is the large-scale secularization of the Bavarian Church property under Duke Arnulf (reigned 907-937). The process is on the basis of monastic alienation lists, which also contain Benefizia comprehensible. The older research put forward the thesis that secularization had led to ducal fiefs being created from church property: Arnulf had seized church fiefs and passed them on to various aristocratic families. This was rated as supportive element of Bavaria’s unity (Mitteis).

In the 11th century Bavaria was wholly in the service of the Reich; For 53 years, the German kings virtually exercised their rule over Bavaria. How any feudal relations of the Bavarian dukes or ecclesiastical institutions, or the deliberate feudal policy of Emperor Konrad II (reg. 1024-1039, emperor from 1027) could have looked like is beyond our knowledge. Secured is only the general finding that feudalism led in the long run to secure the rule of nobility in Bavaria. Most of the genders had little personal property, which is why they could achieve a significant improvement in their position only through major fiefs from the King, the Duke or the Church. As vassals, they were primarily committed to military service.

b) The "Century of the Welfs"

Better insights can already be gained from the 12th century, when the Hohenstaufen kings and emperors operated an extremely active fief policy. It is only now that an intensified writing of fief relations begins. At Reich level, customary norms are recorded in writing. In Bavaria, first written testimonies appear, which refer directly to contractual relations.

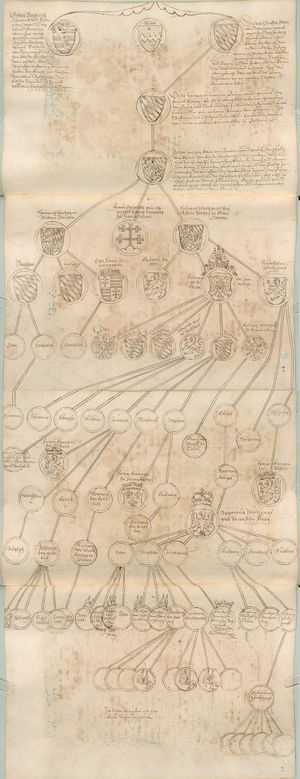

Great uncertainties exist, however, over the rule of the Welfs. It is certain that the Guelph dukes maintained feudal relationships with most of the dynasts or magnates, but not with their nature. Certainly, the ducal feud under Henry the Lion (reigned in Bavaria 1156-1180) was of little importance, since he was hardly in Bavaria and it was only a by-country for him. The up-and-coming Wittelsbachers, on the other hand, created their own fiefdom by investing in the nobility. The most important surviving source of the 12th century is the Falkensteiner Codex, a mixture of traditional and habitual books and lists of fiefs (Noichl). The Codex contains a list of the feudal lords of the Counts of Falkenstein (after Falkenstein, Gde Flintsbach am Inn, district Rosenheim). Among them were several dukes, palatine counts, margraves, counts, bishops and an abbot. There are also fiefs there, which the count has subordinated (so-called after-loan).

c) The role of feudalism in the construction of the Wittelsbach ducal power

In 1180 Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (reigned 1152-1190) entrusted the Wittelsbachs with the Duchy of Bavaria and thus also with the ducal Kammergut. An element of the expansion of the Ducal territorial power, which they had begun with determination, was to inherit the dynastic families who died out remarkably quickly (such as the Andechs-Meranier, the Bogen, the Falkensteiner, or the Wasserburgers). After the sovereign right of resignation to which they were now entitled, the Wittelsbachs withdrew the completed ducal fiefs of these families and took them into their own administration. On the other hand, the confiscation of the ecclesiastical fiefs of the extinct sexes proved to be much more difficult. The resistance of the bishops was broken after lengthy arguments. Only the Augsburgers were able to resist permanently.

The fiefdom of the late Middle Ages

a) Sources and research situation

If there are only a few testimonies about feudalism up to the 13th century, it can be seen in the late Middle Ages, especially in the 15th century "draw from the full". It is only now that precise insights into the structures of Bavarian feudalism can be gained.

- Documents on a loan were issued in exceptional cases as early as the 13th century. They did not prevail until the 15th century. Here is between the "fief letters", which the liege lord exposed to his vassal, and the "fief reverse" to distinguish.

- In the 14th century, the tradition of own books on the fiefs, the lore books, also sets in.

- Another important source are small pieces of paper on which clerks wrote down memorials to lords or vassals themselves called their fiefs and begged for new resignation.

Despite this much larger source base, research is still in its infancy. So far, only the fiefdom of the Bavarian dukes has begun to be studied (Bader, Klebel, Kutter, Wild); The structures of other Lehenhöfe – to call for Altbayern are the four Hochstifte Freising, Passau, Regensburg and Salzburg, various Reichsstifte as Nieder- and Obermünster, country monasteries and at least 50 noble families (eg the Ortenburger, Toerring, Frauenberger Haag, Preysing) – on the other hand only rudimentary (eg Holzfurtner, Klein).

b) The late medieval ducal feudal system

The fiefdom of the late Middle Ages has been practiced in Bavaria – at least as far as the Bavarian dukes are concerned – under customary and agricultural law practices. Thus, in the Upper Bavarian Landrecht Emperor Ludwigs of Bavaria (reigned 1294-1347, as king from 1314) of 1346 several sections dedicated to the feudal system. Lehen administered essentially the ducal law firm. The Lehengerichtsbarkeit was the court court.

c) The feudal act

To a borrowing it came especially when either the Lord’s case (death of the feudal lord) or the Mannfall (death of the vassal) occurred. In such cases the vassals had their fiefs within the year and day "to mute", i.e. the loan had to be renewed by the feudal lord. The loan was made for a fee, "honor", "Reichnis" or "gift" called. The presentation of the objects of the fief still took place according to the traditional habits, whose order had changed, however. The Lehensakt, either at court, on round trips of the Duke of this himself, but also by representatives such. B. Rentmeister, Landschreiber or even carers could be made, consisted of three parts: From the fief certificates it becomes clear that the first investiture was made in the fief. Then the team was to afford. Since this second component does not emerge from the traditional documents, it was certainly no longer important. Most recently, the vassal had to swear fealty and / or make a pledge of loyalty.

d) Rights and duties of vassals and lords

The medieval legal mirrors such as the Saxon or the Schwabenspiegel provided for a strictly (descendant) inheritance right of the vassals to direct male descendants. In Altbayern, however, the conditions were quite liberal. Already in Upper Bavarian Landrecht women are also forfeited. In fact, on the occasion of a man fall, direct female descendants of the vassal and, under certain circumstances, relatives of the side (such as cousins) or siblings could inherit fiefs in Old Bavaria. With the consent of the Duke, the vassals could sell their fiefs. In many cases, the fief issued by the duke was also passed on to the afterva.

The statements of the documents to the fief services are quite general: The vassals should contribute to the well-being or benefit of the duke as lordship, turn damage from him and conceal no fiefs. Whether and to what extent advice and help has been provided can not be answered from the sources. War services of the vassals played virtually no role. Only a few concessions from castles give rise to more concrete obligations such as opening or residency obligations.

The specific duties of the feudal lord remain in the dark. Apart from the duty to provide protection and protection for the vassal and to help him in emergencies, nothing is said from the sources. The Duke was able to withhold home fiefs, so there was no need for a loan.

e) feudal objects and subjects

Particularly characteristic of the late medieval feudal system of the Wittelsbach dukes is the low social level of the vassalage and the low value of objects going to fief. The structure of the vassalage changed. Thus, the share of nobles was only small. Most of the vassals came from the peasant population since the 14th century. In contrast to the nobility held knights’ loans, the bourgeois or peasant fiefs are referred to as loot, since that due at a loan "Reichnis" was to put in a bag. The term "bag feud" Of course, the sources do not appear in the sources until the end of the 15th century. Beutellehen derived either from knights’ sages or from own goods, which had approximated the legal form of a fief and were no longer precisely distinguished from these. Since fiefs could also be converted to their own or Urbargütern, the feudal system is sometimes no longer precisely distinguishable from other rural lending forms or Eigen (Holzfurtner, Faußner).

Significant feudal objects such as court, castles, customs or mining shelves or even offices were hardly awarded. The vast majority of fief objects were agricultural goods, mostly farmed by the peasant vassals themselves, and rights. First and foremost, farms or farmsteads (for example, a half or quarter farm) with associated agricultural land such as meadows or fields and tithing rights have been awarded. Also related to Urbargut, held by farmers interest loans played at least in the Duchy of Bavaria-Munich a role. From interest loans, the vassals had to pay an annual levy to the feudal lords.

f) importance of ducal feudalism in the late Middle Ages

The importance of feudalism for the late medieval duchy of Bavaria can be estimated as rather low. It had the character of a by no means prominent legal form among many, which even partially mingled with other legal forms. The personal element of the feudal system, the binding of the vassal to the feudal lord, receded in relation to tangible components such as the independent processing of the lent goods by the peasant vassals or the taxis incurred during the enthronements. The nobility in the 14th and 15th centuries was already so far attached to the Duke through the office, his activity in the Ducal Council, the landedness and the unity of the Bavarian territory that an additional contractual relationship was no longer mandatory.

Outlook on the modern era

After the reunification of Bavaria in 1506, the ducal feudal system was restructured institutionally and administratively. For the Rentämter lehenpröpste and for the district courts Lehenknechte or Unterlehenpröpste were used. The supervisor went in 1550 on the newly established court chamber (with the installed there Office of the Oberlehenpropstes) over. Since 1779, the Upper State Government and finally since 1808, the Supreme Lehenhof was responsible, which was under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The emergence of the modern governmental state is also reflected in the sources. Thus, since the 16th century, knights and donkeys were clearly divorced from each other, which each had its own lore books result. Ritterlehen the Duke at court, Beutellehen lent the respective Lehenpröpste. The expanding correspondence was also reflected in the systematic management of structured according to fief objects fact files. In the 18th century, finally, a lively fief legislation began.

At the same time, however, the importance of feudalism continued to decline. For the feudal lords it developed into a pure source of income; the personal element no longer mattered. Only the few fiefs granted outside Bavaria by the Elector, "Ritterlehn except Lands" were of a certain territorial interest. On the part of the Bavarian aristocracy efforts in the 17th and 18th century became recognizable to convert fiefs into personal property (to allodify). Affected were also bag lenders, who were able to acquire nobility over Niedergerichtsrechte. The Elector tried to counter that, but with moderate success.

In the course of the transformation of Bavaria and the dissolution of the Old Kingdom since the beginning of the 19th century, finally, almost all fiefs were allodifiziert during a prolonged process. The Lehenedikt issued in connection with the Bavarian constitution of 1808 provided, only Kronämter and larger properties held by aristocrats to receive as fief and to transfer everything else into personal property. However, according to the provisions of the German Federal Act of 1815, smaller knightly loans lent by aristocratic noblemen remained. At first, only the loaves were completely dissolved. It was not until 1848 that the Bavarian state passed a law regulating the replacement of all fiefs. Exceptions were again only the Crown offices and special royal fiefdoms. They continued until 1919/20, when feudal abolition was finally abolished.

literature

- Matthias Bader, The feud of Duke Henry XVI. of the rich of Bavaria-Landshut. A written study on the domination and administrative practice of a territorial principality in the first half of the 15th century (Studien zur bayerischen Verfassungs- und Sozialgeschichte 30), Munich 2013.

- Jürgen Dendorfer, What was the feud? On the Political Significance of Lehnsbindung in the High Middle Ages, in: Eva Schlotheuber (ed.), Ways of thinking and life in the Middle Ages (Munich Contact History 7), Munich 2004, 43-64.

- Jürgen Dendorfer / Roman Deutinger (ed.), The Lehnswesen in the High Middle Ages. Research Constructs – Source Findings – Interpreting Relevance (Medieval Research 34), Ostfildern 2010. (mainly the contributions of Hubertus Seibert, Non predium, sed beneficium esset … The Lehnswesen in the mirror of the Bavarian private customers of the 12th century [with views of Tyrol], 143-162; Gertrud Thoma, Lending Forms Between Manorialism and Leaning Beneficia, Lehen and Feoda in High Medieval Uplands, 367-386, and Roman Deutinger, Das hochmittelalterliche Lehnswesen. (Results and Perspectives, 463-473)

- Roman Deutinger, Observations on feudalism in early medieval Bavaria, in: Journal of Bavarian Regional History 70 (2007), 57-83.

- Hans Constantin Faußner, From Salmann’s Own to Beutellehen. On the landlord property in the Bavarian-Austrian area of law, in: Research on Legal Archeology and Legal Folklore 12 (1990), 11-37.

- François-Louis Ganshof, What is the Lehnwesen? Darmstadt 6th Edition 1983 (French first edition: Qu’est-ce que la féodalité ?, Brussels 1944).

- Ludwig Holzfurtner, The Grundleihepraxis Upper Bavarian landlords in the late Middle Ages, in: Journal of Bavarian Regional History 48 (1985) 647-675.

- Ernst Klebel, territorial state and fief, in: Hans Patze (ed.), Studies on medieval feudalism (lectures and research 5), Lindau / Konstanz 1960, 195-228.

- Ernst Klebel, Free Eigen and Beutellehen in Upper and Lower Bavaria, in: Journal of Bavarian Regional History 11 (1938), 45-85.

- Herbert Klein, Ritterlehen and Beutellehen in Salzburg, in: Communications of the Society for Salzburg Regional Geography 80 (1940), 87-128.

- Christoph Kutter, The Munich Dukes and their vassals. The Lehenbücher of the Dukes of Upper Bavaria Munich in the 15th century. A contribution to the history of feudalism, Diss. Masch. Munich 1993.

- Woldemar Lippert, The German Lehnbücher. Contribution to the registration and feudal law of the Middle Ages, Leipzig 1903 (ND Aalen 1970).

- Heinrich Mitteis, Lehnrecht and Staatsgewalt. Investigations on medieval constitutional history, Weimar 1933 (ND Cologne / Vienna 1974).

- Steffen Patzold, The Lehnwesen (Beck’s series 2745), Munich 2012.

- Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vasalls. The Medieval Ev >swell

Further search

External links

Related articles

Lehensrecht, Lehenrecht, Lehnrecht, Lehenwesen, Lehnswesen

Related Posts

-

Fehdewesen – historical lexicon of Bavaria

feuds The feud was a means in the Roman German Reich to enforce its own law. From the early to the late Middle Ages, the feudal system has undergone…

-

German academy – historical lexicon of Bavaria

German Academy The Academy for Scientific Research and Care of German Studies / German Academy was founded on May 5, 1925 in Munich. Initially focused on…

-

Haus bavaria – historical lexicon bavaria

House Bavaria Emerging term in the late Middle Ages, which also includes the geographical area of the state of Bavaria, as well as the ruling dynasty…

-

Federalism – historical lexicon of Bavaria

federalism Federalism (from the Latin foedus = alliance) is a historical-genetic concept of order that characterizes the field of tension between…