Get A Copy

Friend Reviews

Reader Q&A

Lists with This Book

Community reviews

The book is bound in blood-red linen, printed in black, on the black paper cover ghosts a shadow made of bluish fibers under red letters. It cannot be a coincidence that the book has exactly 666 pages. A hardcover edition of the Nobel Laureate’s Opus Magnum is no longer available and I had to use the second-hand bookshop.

On the first pages there is a thank you to the Satanism researcher Josef Dvorak, on the right opposite three crossed / twisted folds The book is bound in blood-red linen, printed in black, on the black paper cover ghosts a shadow made of bluish fibers under red letters. It cannot be a coincidence that the book has exactly 666 pages. A hardcover edition of the Nobel Laureate’s Opus Magnum is no longer available and I had to use the second-hand bookshop.

On the first pages there is a thank you to the satanism researcher Josef Dvorak on the left, on the right opposite three crossed / twisted ribbons with Hebrew characters. The graphic depicts a meusa, in the Jewish tradition a banner with verses from the Torah, which is fastened in a capsule to protect the house on the right door jamb. Although one can assume that a woman is rather skeptical of Jelinek’s Old Testament rites, the feature pages quickly arose in speculations as to where the magic spell might come from. It was only years later that the editor revealed the secret – the saying came from the author herself and was translated into Hebrew: The spirits of the dead, who had disappeared for so long, are to come and greet their children.

When I recently learned that the children of the dead for the Styrian Autumn (2017) were screened in a film performance by the Nature Theater of Oklahoma (US) at the original locations in the Murzal Valley and in Maria Zell and that they were released in cinemas by Ulrich Seidel as a feature film I decided to finally read the book.

The first few chapters were tedious and irritating. The sprawling and exhausting language as well as some extremely unsavory sales did not awaken my enthusiasm.

Slowly, however, I found myself in a different reading mode and a little later this text swirl pulled me into its depth, devoured me and did not let go of me with its dynamism and intensity to the last page.

The book is completely different from anything I’ve read so far. You cannot consume it, you are asked to constantly question your own point of view, while what you have just read questions or redefines itself. There is nothing to hold onto, characters, plot, context, even language, everything is exposed to the flow of constant change.

"But the cause of every becoming is that it falls into ruin: the god of time. And it came too late today. Time is not so steep. Button harmonica that can be pulled apart and pushed together again. Or yes?"

In any case, the laws of time and space seem to be abolished, characters suddenly play on a different location, what has already happened takes place again, past, present and future cannot be clearly separated, it could be anything different Take place at the same time, which makes me think of Marianne Fritz.

The main characters are neither alive nor dead, only half of them are there, then copies of themselves again. They have wild sex, dismember and eat each other, decay, become transparent, disappear and reappear two chapters later just under the ceiling. I see them as vehicles to convey or map language as on canvases. They also do not embody abstract ideas like in masquerades, they only consist of their names, i.e. again of language (“Let the language speak for itself” says Jelinek somewhere).

It is well known that the content of the repressed Austrian guilt for the mass murders in the Second World War and their (non-) investigation is well known. So one tends quickly to allegorical interpretations of all the dead, half-dead, undead, not yet dead, who populate the novel, as victims or perpetrators of past and present events. The criticism of our superficial media society with its prominent art figures in sports, culture or politics, which often remind of zombies, is also unmistakable. These allegories may be justified, but what matters is the aesthetics of the language, which makes this novel so extraordinary and great.

The language is used “deconstructively” – it cuts, mills, dissects, exposes and reveals, it turns the bottom up and makes unheard of connections audible and unclear visible. This is achieved with a bundle of associations, metaphors, puns, hints and ambiguities, defamation of quotations from advertising, TV series and films, names of well-known people, confectionery, cosmetics and car brands and above all countless intertextual references – again and again the Bible , Plato’s allegory of the cave, Hans Lebert is omnipresent, Paul Celan, Karl Kraus, Elias Canetti, and and and – and all of this tumbles over the pages like an enormous maelstrom, relentlessly and mercilessly.

Jelinek, as a trained musician, also uses the formal language of music, so you can easily recognize the three-part superordinate form as exposure, implementation and recapitulation, the text also contains structures such as repetition, variation, modulation, loops.

As in a symphony, the tone is also varied, sometimes powerful and loud, then ironic, funny to biting, sometimes coarse and vulgar and later again almost lyrical. A washerwoman is standing in the kitchen trying to pull a strand of hair out of her face wipe, like in slow motion, the strand of hair falls back on her face, Gudrun, the undead suddenly stands in the door, puts down her bag, looks up again and "the kitchen has come to life and is running or going there. Gudrun is literally dragged through the window by the eyes, pulled out into the night. She drives on a street !, and the median strip races, dashed lines, an inconclusive path for small and animals (unfortunately, the animals often take the shortcut anyway), also drives to the left of her.”The kitchen and the street mix in a dreamlike sequence. "Gudrun presses herself against the wall so as not to be torn out, she presses her hand to her eyes, but the hand suddenly becomes transparent, and Gudrun feels that the landscape wants to lure it out, pull it out as if it were nothing, and offer no resistance , yes, as if she had always been walking this street, yes, as if she was a street herself ….."However – the idyll only lasts briefly and the slap in the face inevitably, somehow fire comes into play:". as eager as the fire is, which can burn more than 4700 people in a total of 46 combustion chambers over 24 hours, just because it has been given so much to process."

The predominantly authorial narrative constantly changes into the I and also into us, although the personal radius of these I and we does not always appear to be clearly limited. However, the author also uses these sequences to put her own words into perspective and to question them, thus showing her own uncertainty and standing by it. Sometimes the reader is also addressed to you: “. the emptiness, I tell you, it is terrible! You see nothing but your own breath to breathe in again;"

The novel is a poetic symphony in the form of a novel or a baroque memorial and memorial for the dead of the Holocaust cast in language. Only the monument is not erected but dug deep. Jelinek scrapes the high gloss of our brightly colored media world layer by layer, pumps the toxic sludge secreted by politicians and dignitaries out of Sunday speeches to the surface, works its way through the landfill of our forgetting and repressing, down to the darkest abyss, where we finally come across the mountains of corpses , on millions of piled-up skulls and on shelves full of rex glasses with preserved children’s brains.

In spite of all the euphoria, there were places where I reached my limits: because the persistent density led to a state of idling, "frantic standstill" (Paul Virilio) or simply lacked my condition. I did not know that a pilgrimage to Maria Zell is so exhausting (Jelinek stop, have mercy on me, mercy on the tired reader, whose nerve cells are already firing from the last hole!). The author is also aware of this, so she simply breaks off a waterfall from one sentence with “and I find no end again".

Since I refuse to take any reading challenges out of sheer desire to read, I would have all the time in the world to read everything a few more times, to research, to solve all open puzzles, to follow all cross-references, to fathom all the subtleties of form and structure. No, should the Germanists do that, I would like to read other books, and so we are seamless in the popular discussion of what or how much should or should, an author can expect his readers. , , , more

RELATED ITEMS

-

Lebensborn children: a letter from a strange, dead father

In search of his origins: Lebensborn child Peter Meier. (© Michael Kretzer) They grew up in homes of the SS instead of their parents, and that…

-

The last children of schewenborn

Books away from the mainstream “When we drove through Lanthen, everything was still as usual. But it flashed in the forest, especially in the curve at Kaldener Feld…

-

Are there people who make something out of selflessness? Where are you, yahoo clever

I am a Christian and believe in the principle of charity. I’ve believed in it all my life. I actually thought so cold-heartedly…

-

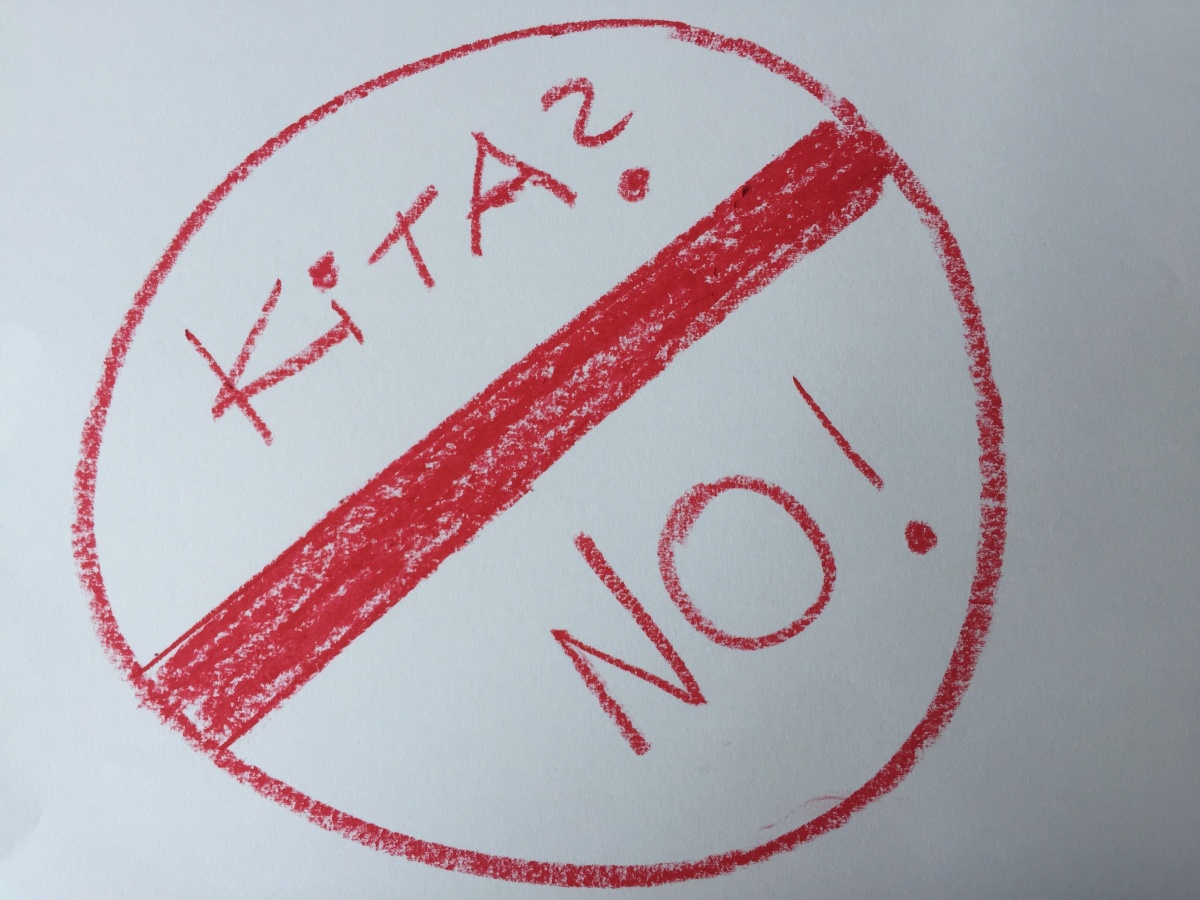

Kita? Not with us: why we don’t send our children to kindergarten, Stadt Land Mama

There are families who consciously choose not to look after their children in kindergarten. Who are those people? By Lisa Harmann The house, in…