It is 7 o’clock in the evening in Gulu, the blazing hot provincial capital of Northern Uganda. The darkness falls quickly here, not far from the equator, and so strong headlights are needed to recognize the extent of the migration that is pushing along the access road into the center of Gulu. It is a sad procession of hundreds of children, most of them barefoot, some with sleeping mats on their heads, the little ones by the hand of their mothers, a few on bicycles. That evening, too, they set out from the surrounding villages to spend the night in the relative security of Gulus. Because outside, in the villages, the rebels of the Lord’s Resistance Army, LRA for short.

By Ludger Schadomsky

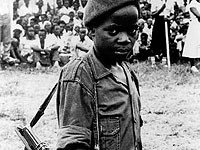

The war of the rebels has been going on for over 17 years: child soldier in Uganda, 1996 (AP)

Michael Oruni is the office manager of the non-governmental organization "World vision". He explains the macabre procession:

We call it "night commuters" – Children, some mothers, a few fathers. They are looking for refuge in the city for the night: in hospitals or schools. They come here every day – they come in the evening and return to their villages in the morning – whether it rains or not.

Now in its 18th year, the LRA rebels are waging one of the most brutal wars in Africa – against the government and against the civilian population of northern Uganda. They particularly focused on kidnapping minors from villages and classrooms and training them as killer machines and sex slaves. No one knows how many children the rebels have lost. Non-governmental organizations speak of up to 20,000 – only that much is known: the LRA’s guerrilla war against the Ugandan government has turned half a million people into internally displaced persons, and they vegetate in camps where alcohol, unemployment and violence prevail.

Later in the evening, visit one of the huge camps, where up to 3000 children find shelter night after night. That evening several hundred of them got together for an improvised school lesson in the open air. To sing is on the program, boys and girls vie with each other for the best lecture: Trauma work packed as an entertainment program.

The 14-year-old Innocent has been commuting from his village into the city since he was one year old – initially on his mother’s back, today on foot or by bike. "Innocent" – that means translated "innocent": But there can be no question of innocence in a generation growing up in a state of emergency.

I come here every day so I don’t get kidnapped. If you sleep outside in the village, the rebels will come and take you to the bush to fight the government. A neighbor of mine has been kidnapped – he has not shown up to this day. As a result of commuting, I’m usually late for school, which means I miss a lot of lessons. And because we are so many here, I keep getting diseases – especially scabies.

Hours of walking through heat and rain, hygiene problems in the camps, lack of schooling: Innocent and the other boys and girls here in the camp can only dream of a normal childhood. And yet: compared to their peers, who were kidnapped by the rebels, they can count themselves lucky.

Faith Kitara, 18, is one of them. She was on vacation when LRA rebels raided her bus and dragged her along with her peers. Faith recalls the hardships and hardships of the following months:

There was no salt, neither soap nor water. We drank our own urine and ate leaves to stay alive. Many girls have become pregnant and have given birth in the bush. Some left their babies behind because they could not feed them. We had to march for days, it was terrible.

Faith was 14 when she was kidnapped. Like most female victims, she became a rebel leader "Mrs" given – a euphemism for sexual exploitation. The young woman is lucky that she only contracted syphilis and not AIDS. But the initiation rite that Faith had to undergo was much worse.

You told us. If you don’t kill, we will kill you. One day we met a woman in a village, she was pregnant. The rebels ordered her to give up salt and pots. When she disobeyed, they ordered me to dismember the woman with the machete. I begged, but they said: If you don’t kill them, we will kill YOU. In the end, they allowed me to shoot the woman instead of dismembering it. Then we had to collect everything edible and took some boys and girls from the village with us.

The stories of the Gulu child soldiers are so gruesome that one may want to doubt their truth: there are reports of children who were forced to play volleyball with a severed head. Others had to bite fellow prisoners to death.

Stories like this are part of everyday life for Samuel Mkungo, one of the trauma specialists in the World Vision team. In its detention center in Gulu, the non-governmental organization takes care of kidnapped children – including money from Germany – who managed to escape or who were liberated by the army. In the camp, the children receive medical care, care and psychological care. Many don’t dare to talk about their experiences – out of shame. So Samuel and his colleagues let the trauma team paint the little ones:

A girl painted this picture. The picture shows a violent kidnapping: someone’s head is cut off with a machete, bound school children are led out of one school into the bush, a woman is shot, another is kicked, and the huts in the settlement are set on fire. Many of the children find it easier to express their experiences through painting. They don’t want to talk – so we’re trying to get the stories that way.

Who is this now? "Lord’s Resistance Army", who has terrorized an entire area for 18 years and driven hundreds of thousands out of their villages? The group has its roots in a quasi-religious sect, in which political opponents of Yoweri Museveni gathered in the mid-1980s. The rebels of the National Resistance Movement had previously overthrown General Tito Okello and established themselves in the capital, Kampala. Because supporters of Okello’s reprisals from the north "Südlers" Museveni feared, fled to the north and launched attacks against the new government from there.

In 1988 the resistance fighters formed in the Lord’s Resistance Army under Joseph Kony, a former Catholic priest. Its stated goal is to overthrow the Ugandan government and to proclaim a state of God based on the Ten Commandments. Should one call it cynical, perverse or simply crazy when someone who pretends to be a man of God, of all people, does the bidding "You should not kill" trample like this?

In view of the ongoing massacres, more and more Ugandans are asking ever more loudly why the Ugandan army is unable to render a guerrilla force, the hard core of which is estimated at just 300 fighters, harmless. After all, Uganda – a close ally of the Americans in the fight against terrorism – receives massive military aid from Washington – and was even intended for this purpose for reconstruction contracts in Iraq. Should there be something wrong with the rumors that political, economic and geostrategic reasons speak against an end to the war ?

There is no doubt that Uganda’s President Museveni, who has headed a so-called one-party democracy since 1986, uses the war to expand his own power base and silence critics. Uganda today presents itself as a deeply divided country. In the south, many suspect the northern people of making pacts with the rebels. In the north, on the other hand, the political class in Kampala feels neglected. This, and the fact that the Ugandan army has repeatedly been guilty of serious human rights violations in the north, is a significant explosive for Museveni’s one-party rule. Critics accuse him of preventing political mobilization of the North through the war. And so, announcements that they want to negotiate with the LRA rebels have so far turned out to be lip service.

The Spanish missionary Father Carlos Rodriguez has been working in Uganda for 16 years. He is a member of the "Acholi Religious Leaders ’Peace Initiative", an interdenominational peace movement of Christian and Muslim groups in Northern Uganda. It has set itself the task of mediating between the warring parties. However, although the government officially recognizes the mandate of church leaders, it has repeatedly torpedoed attempts at conversation in the past. The churchman senses treason – with the approval of the highest authorities:

Many army officers do a bomb deal with the war. Then there is the neighbor Sudan, who is interested in the presence of the LRA. Because they are fighting the South Sudanese rebels of the SPLA. For years they have been given weapons by the Ugandan government, which uses the war in the north as a pretext. The Americans are behind it, using their ally Uganda as a middleman.

A classic proxy war, fifteen years after the official end of the Cold War, fought on the back of underage children. It has been well documented that the LRA has received military and logistical support from Uganda’s neighbors Sudan since the mid-1990s, despite repeated denials from Khartoum. Because the rebels of the LRA helped the Islamist regime to fight the SPLA’s own insurgents in the Equator Province.

In late 2001, the State Department in Washington officially named the LRA "terrorist group" classified. In March 2002, the Sudanese government subsequently committed to "Sunshine policy" any towards the US support to discontinue the LRA. The promise was of course not worth a chanter: The arms deliveries to the LRA were soon resumed – with the result that 8400 children were kidnapped by the LRA in the period since June 2002 alone.

In addition to this human tragedy, the war is causing great financial sacrifices from a country that can hardly provide basic services to its citizens. John Baptiste Odama is the Catholic Archbishop of Gulu and also Chairman of the "Acholi Religious Leaders ’Peace Initiative".

This war cost Uganda $ 1.3 billion. That is a huge sum. We threw that money out the window. First we destroy everything – and then we spend so much money on the reconstruction. We therefore advocate peace talks – they take longer, but are cheaper.

To protest his government’s warfare and ignorance of the world community, Odama spent an night outdoors with the commuters from Gulu last year.

The action was an outcry. To the rebels: why are you killing us? To the government: why don’t you help us? And to the West: why don’t you come to our aid?

But the demands for a solution at the negotiating table fall on deaf ears in Kampala: The Ugandan government continues to rely on the military card. The minister responsible for the reconstruction of northern Uganda, Grace Akello, defends the hard line:

The rebels are still supported by Sudan and have retreat bases there. That is why we are pursuing a military solution and we have no other choice. The LRA only understands the language of violence. So we have to answer in the same language.

Many see it differently in Uganda today, especially since there have been no military successes. In March 2002, President Museveni launched the "Operation Iron Fist". The rebels should be crushed with heavy equipment. But Uganda’s armed forces embarrassed again, whereupon an angry President Museveni changed his leadership. However, the rebels were not impressed and struck again: in February, the LRA attacked the Barlonya refugee camp and massacred 200 civilians – the worst attack by the LRA in eight years.

It was this act of blood that brought the International Criminal Court to the scene. That already had in January first permanent genocide tribunal in The Hague followed an invitation from the Ugandan president to investigate human rights violations in northern Uganda. The so-called invitation was necessary because the tribunal can only take action on the initiative of a country.

The day after the Barlonya massacre, the prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, promised to clear up the incident. In addition, he announced an early official investigation for Uganda.

While the Ugandan government euphorically welcomed the announcement of an official investigation by the Hague Tribunal, peace activists in the north raised the alarm: The Acholi Leaders’ Peace Initiative issued a statement warning that.

. An investigation and a possible international arrest warrant would shut the door to a peaceful solution to this long conflict forever.

In doing so, she distances herself from organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, which expressly welcome a criminal court investigation. This would send out a significant political signal, although it cannot bring a solution to the conflict. Faced with Kony’s refusal to come to the negotiating table and Kampala’s determination to resolve the armed conflict, mediators are now looking to neighboring Sudan. A final peace agreement between the Sudanese government and the rebels of the SPLA in the south – according to the calculation – could cut off the LRA’s bases in the neighboring country, rendering them meaningless.

Last Friday, representatives of the Sudanese government and the rebels promised in a memorandum that they would sign a comprehensive peace agreement for South Sudan by the end of the year – which should have happened in the summer. However, both sides remained vague and the UN Security Council’s threats of sanctions were weak.

So while the conflicting parties in Sudan continue to negotiate, psychologists and social workers in northern Uganda are trying to integrate former LRA child soldiers. Psycho-social rehabilitation measures are not sufficient in the long term – the young people must be enabled to earn money.

But hundreds of children are still in captivity. Like the residents of Acholiland, they hope to see peace soon in neighboring Sudan. A signature on a peace treaty for South Sudan and a solution to the Darfur crisis could end two of Africa’s bloodiest wars in one fell swoop. It remains to be seen whether the Ugandan government’s latest peace initiative will survive: President Museveni surprisingly announced a unilateral ceasefire to give the LRA leadership time to think at the negotiating table. At the same time, Museveni announced that he would protect Kony and the LRA leadership from an investigation by the International Criminal Court. The conciliatory gesture prompted violent protests, such as the human rights organization Amnesty International. But the excitement is superfluous: once invited, the criminal court cannot be unloaded again.

In August, representatives of the International Criminal Court traveled to Uganda for a first inventory. Incidentally, if the prosecutors of the Hague Tribunal start their official investigation at the earliest in early 2005, then they should also visit the Ugandan president. Because its government is also on the red list of UN child protection. Secretary-General Kofi Annan personally accused in a report to the Ugandan Army Security Council of continuing to recruit child soldiers and thereby violate several conventions. Many child soldiers serving in the Ugandan army had previously been rescued from the hands of the LRA, according to human rights groups – only to be subsequently recruited into the regular army: a particularly perfidious method of what is supposed to be so praised in the West "flagship government" Uganda. Evil tongues also claim that the fear of visiting the Hague Tribunal is the real reason for Museveni’s sudden willingness to talk.

RELATED ITEMS

-

Child soldiers fight in 14 countries, world, dw

Around 250,000 girls and boys are forced to fight worldwide. They are abused, they kill and they die. On the part of rebels, however…

-

Children in one world: children in war 1

Internet project work: A class 6A web log from the Rudolf Diesel High School in Augsburg on the topic of children in one world Thursday, March 03, 2005…

-

Children are very often victims of war and armed conflict. They are often victims of violence. They are mostly child soldiers…

-

Small hands, big weapons: child soldiers worldwide, world, dw

Every year on February 12, Children’s Soldiers Day commemorates the many young people who take part in armed conflicts worldwide. The…