House Bavaria

Emerging term in the late Middle Ages, which also includes the geographical area of the state of Bavaria, as well as the ruling dynasty Wittelsbach. The training of a consciousness of a "House Bavaria" went hand in hand with the genesis of a largely closed territorial state in Upper and Lower Bavaria. Despite different interests and ambitions, all of Wittelsbach ‘s partial lines, including those in the Palatinate, identified with the "House Bavaria".

Table of Contents

The establishment of the house term in the late Middle Ages

The term "House" is from the late Middle Ages in addition to its original meaning for the princely or noble "gender". Closely related to this is the term "country" as a territory belonging to a ruling dynasty, in which the existing legal bases had receded into the background.

With the political and administrative transformations of the 15th and 16th centuries, this interconnectedness became increasingly obsolete. A legitimative brace was needed to unify claims to rule and land. These could be subsumed under the house term: Thus, from the geographical state of Bavaria and the ruling since 1180 dynasty Wittelsbach the "House Bavaria" (First document under Ludwig the Bavarian, reg. 1314-1347, emperor since 1328). With this term, the legitimacy of the stress on both components – land and rule practice – was demonstrated.

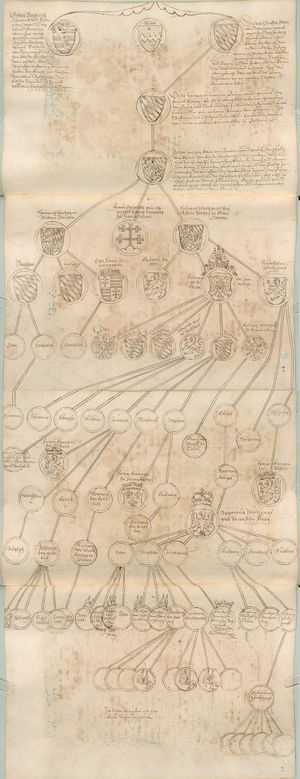

Crucial for the house term was that he had both a dynastic-lordly implication, as well as had to work geographically-territorial. For the Bavarian Wittelsbacher, the concept of the house was therefore easily applicable: they could construct a close connection between the land and the dynasty through numerous genealogies and agnatic lineages. In the case of other dynasties, this proof was more complicated, as in the case of the Hohenzollerns. These could not rely on a long tradition of rule in a traditionally suspected area, so that the house term was difficult to apply and prevailed only slowly. Thus, it was not an expression that could be used at will, in order to comprehensively describe individual constituents, for certain conditions had to be met for legitimate use. The connection between ancestral territory and actually exercised rule had to be credibly transported and propagated.

Comparison with the house term of the Habsburgs

The formulation of a house term was found in the late 14th century already in the Habsburgs, the term "domus austria" used in their deeds. This rather early use of an abstract concept was due to the fact that the rule of the dynasty "Habsburg" was not equated with the rule over a geographical area "Austria". After the Roman-German king had been a Habsburg for almost 300 years since Albrecht II (reigned 1438-1439), it had become necessary to combine the claims to power as Duke of Austria with those of a king over the widely ramified empire. The geographical connection was indeed present, in contrast to Bavaria but much less clear: Although Austria was the reference point of the Habsburgs, but the actual dominion could be designed more spacious.

Due to the marriage of Maximilian I (reigned 1486-1519, emperor since 1508) with Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482), the term was further extended: Zu "House Austria" now came that too "House Burgundy", again with the emphasis on the regional component. For a short time, the unity of the two houses should be the title of a kingdom "Austrasia" be generated, but eventually sat down "House Habsburg" as an umbrella term, which in turn emphasized the dynastic component.

Use of the term in Bavaria in the 14th and 15th centuries

The household name has been reinforced since the late 14th and in the 15th century in Bavaria and, above all, deliberately used. Reinhard Stauber defines "House Bavaria" as follows: "The term ‘Haus Bayern’ thus depicts a close connection between dynasty, country and subjects as postulated in a kind of timeless, higher reality. Bavaria is thought of as a house, a country, and even a kingdom that has always played an important role in the Western Empire. “(Stauber, Staat, 546). This house term contained the gender of the Wittelsbacher with all its lines "as well as the entirety of the Wittelsbach countries in the context of the old Bavarian duchy, thus the total Bavarian dominium" (Weinfurter, unit, 228). The fragmented dominions of the Wittelsbach lines in the Palatinate were also included. In contemporary historiography, all partial lines are taken equally into account in descriptions and chronological recordings. In the performing arts, too, this awareness of a unified Bavarian house was reflected (for example in the picture cycle of the former Fürsten Hall in the Alten Hof in Munich). The realpolitische application of the house term apart from the linguistic and picture programmatic but often turned out differently, since the Hausbewusstsein was different strong with the respective lines.

Bavarian mythical first dukes Bavarus and Norix. Fig. From: CXCIV Illustrations from the Regent’s House Pfalzbayern with text in prose and verse, early 16th century, fol. 1v. (Bavarian State Library, Cgm 1604)

Picture cycle from the Fürstensaal of the Old Court in Munich, the remains are now in the Bavarian National Museum. The fresco was probably commissioned by Duke Sigmund (reigned 1460-1467) and shows over 60 Bavarian princes, starting with the legendary Prince Bavarus. (Photo: Bavarian National Museum)

Reasons for building a home awareness in the 16th century

The education of this consciousness under Duke Albrecht IV (r. 1465-1508) is probably due to the changes in the political structure of the empire. The move to geographically organized territories, which was fully developed from the sixteenth century, required a theoretical and theoretical superstructure to legitimize decisions in the sense of the dynasty. The acting of a prince did not happen out of his own good will, but orientated itself best for subjects, country and also dynasty, just that "House". Albrecht IV predominated in Bavaria with regard to the preservation of the territory and dynastic continuity. This does not mean that in the decisions the claims of the subjects would have been ignored from the outset. But for a ruler like Albrecht, the higher goal was sometimes more weighty. This was the, "House Bavaria" with the support of the other Bavarian princes in the former borders to expand (see agreement between Albrecht and George, Kop oo O., 21.12.1480). Albrecht oriented himself here on the borders, which Bavaria had had under emperor Ludwig the Bavaria, who was model of the most glorious representative of the wittelsbachischen dynasty. He saw himself genealogically as well as politically as direct heir of the emperor and claimed with this reason in the Landshut War of Succession the entire inheritance for himself (Moeglin, Blood, 485 f.). The dynasty was no longer in the foreground in the sense of a home consciousness, but formed only a component to be considered in the program of the ruler. This legitimacy was possible through the direct reintegration of the ruling dynasty into the territory. With which value the individual building blocks "country", "territory" and "dynasty" however, were weighted, was different. Albrecht’s actions in the Landshut War of Succession and above all the provisions of the primogeniture order of 1506 show to a certain extent the manifestation of the idea of the house: The duchy of Bavaria, reunited after 1505, which surrounded all former duchies, was no longer to be divided among various rulers. The sole ruler in the future was primarily the Duke’s firstborn son.

The house term as a demonstration of power

Another conceptual dimension that the "House Bavaria" was the linguistic demonstration of power. Since all members of the widely ramified Wittelsbach family were involved in this conceptual construct, the dynasty appeared as a unitary power, as a politically enormously weighted block that could also be perceived as a threat. For example, the common expansion policy of the Bavarian cousins Albrecht IV and Georg the Rich (reigned 1479-1503) can be referred to individual application examples of this demonstrative unit. Even if the territorial orientation differed: the morally binding and politically demonstrated unified thrust remained under one common goal. In Bavaria, too, the term house acted as a link between the history of the country and the history of the dynasty. Both were now interwoven and thus postulated a joint responsibility of the individual sub-lines: It was in the overarching sense no longer spoken by the Upper Bavarian or Lower Bavarian line, but by the "House Bavaria". Despite all divisions and family disputes, the subsumption was accepted as a household term. So all the dukes bore the same title, viz "Palatine at the Rhine, Duke in Lower and Upper Bavaria". The order of the titles was variable and varied depending on the territorial dominance: Albrecht called himself "Duke of Upper and Lower Bavaria, Palatine at the Rhine"; his Lower Bavarian cousin George preferred "Duke of Lower and Upper Bavaria, Palatine at the Rhine". However, this unit was only related to the theoretical external effect and did not assume that there would have been uniform interests.

Practical implementation

The political practice could not be aligned uniformly for the sole reason that the lines clearly differ from each other purely from the territorial conditions. As an example, it should be noted that the expansion policy of the Munich line turned south, to Tyrol, the Landshuter line, however, to the west, to Swabia. The connecting element was the desire for expansion, not its design. So you can not speak of an overall interest in the Mittelwittelsbach. For what the house concept was however well usable, was the mentioned power demonstration to the outside. In addition, the members of their own dynasty were the first point of contact for support issues. This in turn reveals the expansionist policies of the two Bavarian lines. The fact that this understanding of house concept also included the Palatine Wittelsbacher, shows the strong orientation of Duke George in the 1490s in this direction. After he had turned away from the originally close cooperation with Albrecht, he sought support there now.

"House Bavaria" vs. "Country Bavaria"

An acting of the "House Wittelsbach" was badly possible because this was geographically torn. For this reason, the concept of the "House Bavaria" also because the basic idea of a house term was to demonstrate the close connection of the dynasty to the territory. The mere consciousness of belonging to a common dynasty, which may be accepted on the basis of a common title and coat of arms, was not enough for real political action, but was still in its infancy. For the 16th century one was content with first attempts, for example, with mutual hereditary appointments and marriages, as the example of the marriage of Lower and Upper Bavarian daughters in the Palatinate shows. Other covenants were not made out of a sense of togetherness, but emphasizing that these were necessitated by external circumstances. These agreements were not necessarily on firm foundations, paging or breaches of contract were quite possible. The reorientation of Duke George from Munich to Heidelberg in the 1490s exemplifies this. It was only in the 18th century that the sense of belonging was emphasized more strongly, as mutual inheritance claims had to be supported by arguments.

In the course of the Landshut War of Succession, the term was then given a whole new rating, as he served both the Munich and the Heidelberger line to justify the respective claims to power on the Lower Bavarian heritage. The term was thus not only the demonstration of power of a unit, but could also be instrumentalized depending on the mixed situation and thus to a certain extent perverted: under the legitimizing cover of belonging to one "House Bavaria" self-serving claims were made per line.

literature

- Franz Fuchs, Das "House Bavaria" in the 15. century. Forms and strategies of a dynastic "integration", in: Werner Maleczek (ed.), Questions of Political Integration in Medieval Europe (Lectures and Research 63), Ostfildern 2005, 303-324.

- Katrin Nina Marth, The dynastic policy of the House of Bavaria at the turn of the late Middle Ages to modern times. "To improve the praiseworthy hawse’s brain, increase and enlarge. ", Munich 2011.

- Jean-Marie Moeglin, “The Blessing of Bavaria” and the Reclamation of the Bavière in 1505. Les falsifications historiques dans l’etouranges du duc Albert IV (1465-1508), in: Counterfeits in the Middle Ages, Vol. 1 (MGH Schriften 33.1 ), Hannover 1988, 471-496.

- Jean-Marie Moeglin, Les dynasties princières allemandes et la notion de maison à la fin du Moyen Age, Les Princes et le pouvoir au Moyen Age. XXIIIe Congrès de la S.H.M.E.S. Brest, may 1992 (Société des Historiens Médiévistes de l’Enseignement Supérieur Public, Série Histoire Ancienne et Médiévale 28), Paris 1993, 137-154.

- Stefan Dicker, national awareness and current affairs. Studies on the Bavarian Chronicle of the 15th Century (Norm and Structure, Studies on Social Change in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period 30), Cologne / Weimar / Vienna, Böhlau 2009.

- Katrin Nina Marth, The dynastic policy of the House of Bavaria at the turn of the late Middle Ages to modern times. "To improve the praiseworthy hawse’s brain, increase and enlarge . " (Forum German History 25), Munich 2011.

- Cordula Nolte, family, farm and rule. The kinship relationship and communication network of the imperial princes on the example of the Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach (1140-1530) (medieval research 11), Ostfildern 2005.

- Reinhard Stauber, representation of power and dynastic propaganda by the Wittelsbachs and Habsburgs around 1500, in: Cordula Nolte (ed.), Principes: dynasties and courtyards in the late Middle Ages; interdisciplinary conference of the Chair of General History of the Middle Ages and Historical Auxiliary Sciences in Greifswald in conjunction with the Res >swell

- Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Kurbayern Outer Archive 971.

- Agreement between Albrecht and Georg, Kop. O. O., 21.12.1480 (pfintztag sannd Thoman de (s) holy (en) zwelfpoten day); BayHStA Munich, Kurbayern Outer Archive 971, fol. 35-35, here fol. 35.

Further search

External links

Recommended citation

Katrin Marth, Haus Bayern, published on 06.08.2019; in: Historical Dictionary of Bavaria, URL: (14.11.2019)

Related Posts

-

Fehdewesen – historical lexicon of Bavaria

feuds The feud was a means in the Roman German Reich to enforce its own law. From the early to the late Middle Ages, the feudal system has undergone…

-

Robber knights – historical lexicon of Bavaria

Raubritter Raiding knights are understood to be nobles who allegedly had been in need in the late Middle Ages because of the general social change and…

-

Leaning in old Bavaria – historical lexicon of Bavaria

Leaning in Old Bavaria Already in the early medieval duchy of Bavaria elements of feudalism (vassals, benefices) are attested; the classical expression…

-

Globe of martin behaim – historical lexicon of bavaria

Globe of Martin Behaim Elder Got World Globe made in Nuremberg in 1492/93. The globe was commissioned by the Nuremberg City Council under the guidance of…